Spiritual Insfrastructure

Mauricio Quirós Pacheco in conversation with Tatiana Bilbao

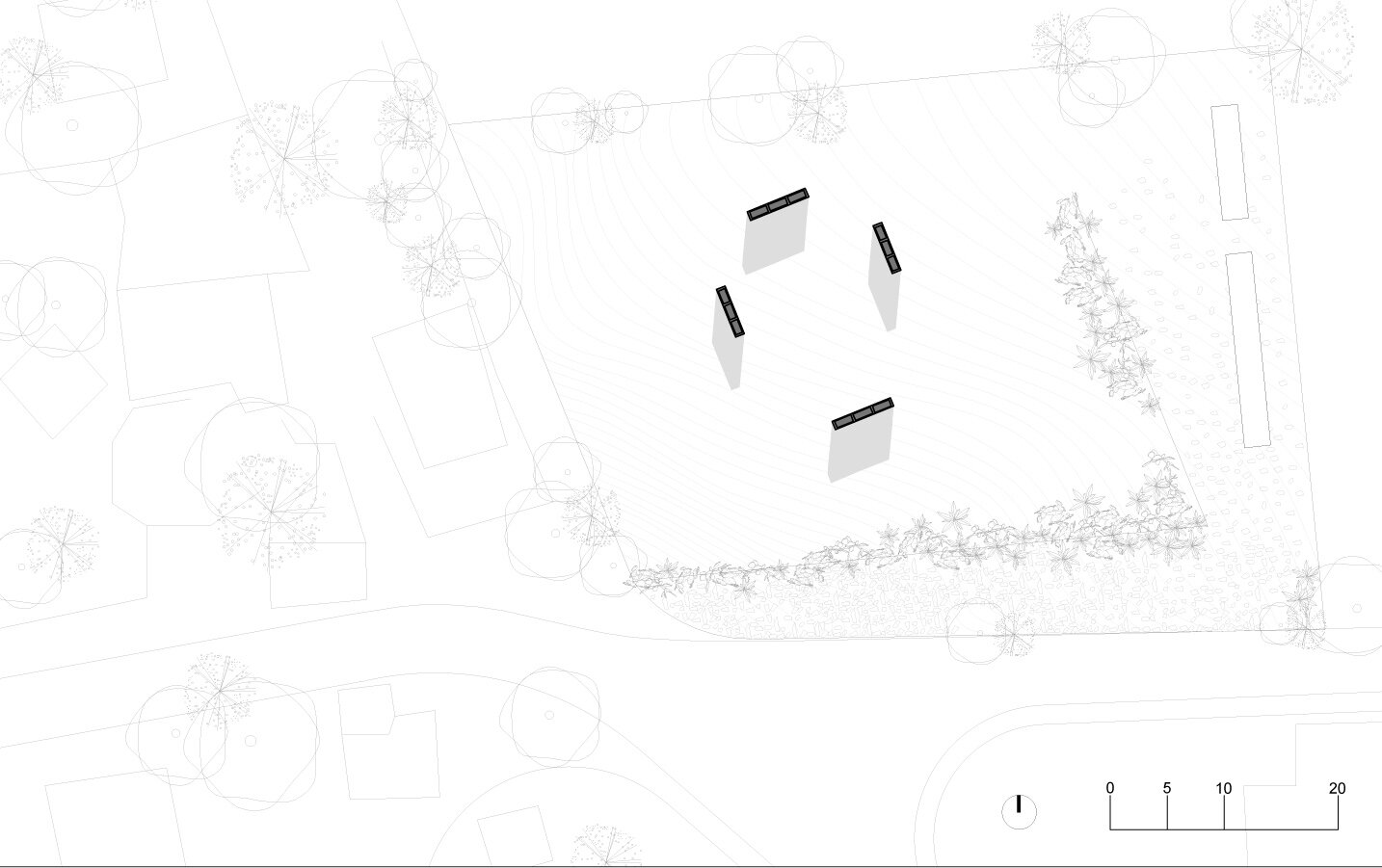

Gratitude Open Chapel

Photo: Iwan Baan

Every year, during the month of March and Holy Week, around three million Mexicans from all over the country embark on a 117-kilometer pilgrimage named the Ruta del Peregrino. Here, pilgrims often walk for several days through the harsh landscapes of the mountain range of Jalisco—starting in the town of Ameca, ascending to Cerro del Obispo located at an altitude of 2000 meters above sea level, crossing the peak of Espinazo del Diablo, and descending to the town of Talpa de Allende—to visit, in an act of devotion, faith, and gratitude, the image of Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Talpa.

In 2008, the State of Jalisco commissioned Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao (in collaboration with Derek Dellekamp) to prepare a master plan to improve the conditions of the Ruta del Peregrino and maximize its social and economic yields. The project, currently nearing completion, is a collection of infrastructural, ecological, and architectural works—each envisioned by a different designer—that supports a single spiritual journey and accompanies pilgrims through a landscape that delivers both penitence and purification. Manifest sat down with Bilbao to discuss the Ruta del Peregrino and its layered ambitions.

Mauricio Quirós: You have mentioned that the Ruta del Peregrino project could only happen in Mexico. What was this “Mexican context” that defined the project so specifically?

Tatiana Bilbao: I think that the Ruta del Peregrino is the result of very particular cultural, religious, political, and social conditions at play in Mexico. First, Mexico is a fervently religious country. For the 95 percent of the population who define themselves as Catholic, religion is a fundamental, deeply ingrained, part of life—even if this fervor is not often expressed externally, but experienced from within. In contrast to this overwhelmingly religious population stands a government that is officially secular and, in theory, banned from investing public resources into any religious institution or project—and there is a lot of public scrutiny and control over the use of funds. The Ruta del Peregrino stood right in the middle of this paradox. In fact, the government decided to move forward and support the project only because it would have a positive impact on more than three million people, regardless of whether they were religious or not. The combination of these elements and their careful management—in addition to a very precise architectural response—makes this project quite unique.

MQ: The Ruta del Peregrino is a religious pilgrimage in which architecture and the landscape play an important role. What was your approach in structuring and conceiving the project?

TB: I don’t think that the role of the architecture, in this case, was to define or regulate the pilgrimage. In fact, it was the other way around; the pilgrimage has been happening for at least two hundred years. We did not conceive the project to change, in any way, the course of the pilgrimage or to influence any of the rituals. It would have been very pretentious to do so.

Our greatest challenge was to project something that, if carefully done, would not alter or control the pilgrimage but somehow complement it. The main objective—and so far this has not been fully achieved—was to provide the pilgrims with infrastructure, with services. We envisioned several shelters, some of which are already built, and landmarks—places for reflection and encounter—to ease the pilgrimage and make the experience more welcoming, and, if you wish, more legible. But we did not intend much more.

MQ: But I do think that the architecture did change, or at least redefine, the landscape in which the pilgrimage takes place. There seems to be a clear intention of making the landscape more architectural, and at the same time, turning architecture into an intrinsic fragment of the landscape.

TB: Yes, I agree. Our intention was also to alter the landscape so that through this new relationship between architecture, nature, and the site the pilgrims would discover new places of encounter, where you could gather with your family or simply stop to think or contemplate. Again, our main purpose was to create a system that would accompany and support the pilgrims across their route.

MQ: Religion in Mexico—and I think this is the norm in most of Latin America as well—is heavily steeped in imagery.And yet, your project is exceptionally abstract.What was the thinking behind the use of such pared-down forms here?

TB: In this case, the reasons were political. The Mexican state is officially secular and cannot endorse or allocate resources towards any religious projects. Just imagine that a few years back there was a big controversy because the then-president Vicente Fox attended mass on Sundays. If he is a practicing Catholic, why is this a problem? Well, in Mexico, the separation between state and religion, which probably has its roots in the Spanish conquest and colonization, was formalized after independence, as religion was outlawed constitutionally from state affairs. The idea of a secular state in Mexico is, ironically, very sacred. This is one of the reasons why the State of Jalisco described the Ruta del Peregrino’s projects as “sites for reflection.” We could not build literal “chapels” or “churches” because they can only be projected, financed, and maintained by the church. To do so, we would have had to involve the church, and automatically we would have lost any financial support from the government.

MQ: What is the current status of the built project

TB: About 80 percent of the “sites for reflection”—landmarks or reference points—are finished and we are at around 20 percent of the overall investment in infrastructure. We had a moment of impasse because every time a new government is elected, the new administration tends to stop or erase what was done before to start afresh. It seems, though, that the new Secretary of Tourism is interested in the Ruta del Peregrino and works will begin again soon, but it has been on full stop for two years. Apparently, we will be able to finish the “sites for reflection” and complete around 40 percent of the infrastructure. The infrastructural works are the most ambitious part because we have several shelter projects and sites of which we have built only two out of eight, and we are still missing various services and food areas, designed by Emiliano Godoy. We also need to do all the landscape work.

MQ: Are there still important landscape elements missing?

TB: Not exactly. I would not call them landscape elements. We are talking more about regeneration strategies for sites that are really rundown; about establishing a garbage collection system, about producing, with this waste, organic fertilizers to strengthen the existing landscape. It is more about revitalizing, strengthening, and supporting the existing landscape, and creating a system that can sustain itself. But, yes, all of this is still missing.

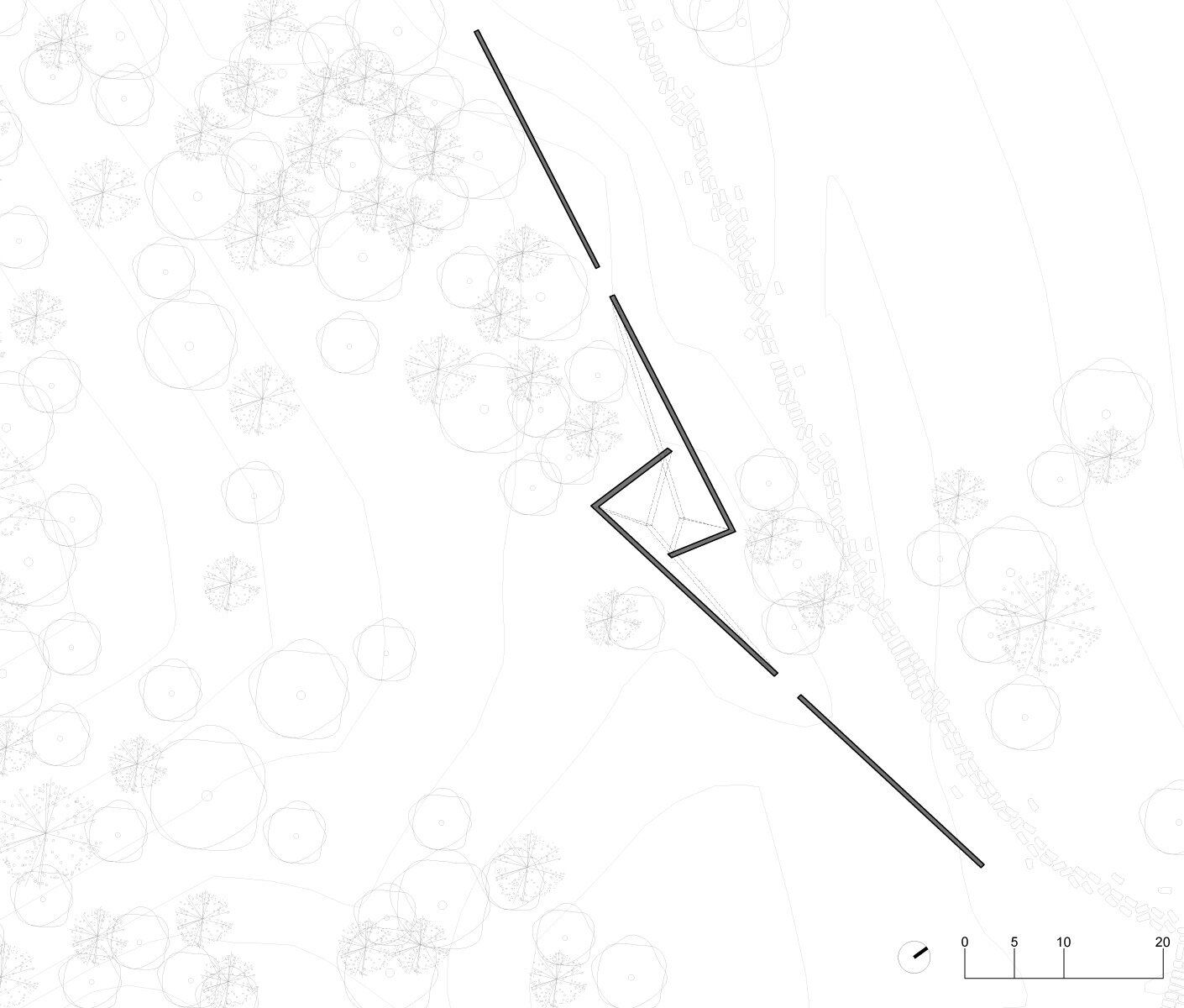

MQ: You designed two projects within the Ruta del Peregrino—the Gratitude Open Chapel and the Mesa Colorada Sanctuary—that are quite dissimilar, one being vertical and orthogonal while the other is horizontal and angular.Why did you adopt these two different design approaches?

TB: The Gratitude Open Chapel—the first built project—was done in collaboration with Derek Dellekamp, so it is the product of “two heads.” It was an extremely delicate project because it accompanies the pilgrim in that initial, critical moment when he or she has decided to embark on a four-day spiritual journey. The government, even before they called us, wanted to create a Sculpture of Gratitude to provide a landmark for reunion; to create something that evinced the beginning of the pilgrimage and that was somehow distinctive. We not only projected this but also created a place for reflection—hence the name Gratitude Open Chapel—that would be visible from other places along the route. We were also interested in providing a very subtle element for pilgrims to reference the extent of the travelling they had already endured.

The Mesa Colorada Sanctuary, on the other hand, is a site that you encounter along the path when you have been walking for two days, more or less. In this case, we were interested in creating an angular and horizontal structure to provide refuge. It was not critical to make it visible from afar, but rather that you encountered the resting point naturally along the way.

MQ: In addition to the Ruta del Peregrino, you have two other recent projects that seem to address the question of “the sacred” in very different ways and in very particular contexts. I am referring to the Observatory House—for artist Gabriel Orozco and inspired by the Jantar Mantar Astronomical Observatory—and Exhibition Room—a project in memory of Ai Wei Wei’s father, in China. How did you reconcile these different approximations with your own views?

TB: Let’s talk about the first one. Gabriel Orozco knew exactly what he wanted from the project right from the start. He had decided to adapt the scheme of the existing Indian observatory to his site and to the particular necessities of his house. What I did, to put it somehow, was to ‘build’ it, to help him define the spatial organization, planning, construction, etc. It was an interesting process, though. The project was always conceived more as part of his artistic oeuvre than a classic architectural work. In retrospect, however, I do think it is an architectural project—a work of architecture, if you will—because it has all the qualities needed for ordinary inhabitation to happen in a comfortable and natural way. Actually, I think it was this potential for adaptation that triggered Gabriel’s fascination with the original observatory in the first place.

The project for Ai Weiwei was different. Interestingly, he liberated us at the outset from having to commemorate his father’s memory in a traditional way. Weiwei, instead of doing a memorial, which was what he was initially commissioned, decided to do a park. He invited various architects to do basically what they wanted within this park. He genuinely believed that this was the best way of honoring his father’s memory.

As for the Ruta del Peregrino, we were freed from any religious or symbolic mandates at the very moment that the government decided to conceive and fund the project as “infrastructure.” Of course, we subsequently dealt with the inherent religious and spiritual aspects of the pilgrimage by creating the landmarks and sites for encounter and reflection that we already discussed. But, again, they are more about complementing the landscape and supporting the pilgrimage than about creating religious objects or spaces.

Gratutude open chapel

Photo: Iwan Baan

MQ: Luis Barragán, in his acceptance speech for the Pritzker Prize, discussed the role of religion and myth in the creation of art and architecture, saying: “it is impossible to understand art and the glory of its history without avowing religious spirituality and the mythical roots that lead us to the very reason of being of the artistic phenomenon.…The irrational logic harbored in the myths and in all true religious experience has been the fountainhead of the artistic process at all times and in all places.” What role do you think religion, or “the sacred,” plays for the new generation of Mexican architects? How would you position your own work and projects within this discourse?

TB: I believe that Barragán was an incredibly religious person, very spiritual. Therefore, in his case, it was religion that provided the foundations for the creation of art and architecture. He saw, worked, and defined the world through this religious filter. However, in my case, it is the exact opposite: I am not a religious person at all. In fact, I am officially a “Catholic” because of my grandmother, not even because of my parents: she drove me, clandestinely, to do my first communion because my parents did not like the idea at all. But, this story aside, I grew up in a completely secular world with no particular relationship to any religion. Of course, given the Mexican context, I do understand that religion is a subject that needs to be addressed with deep respect and care. In fact, it is this attitude of respect that drove me to collaborate with other people for the Ruta del Peregrino, people who could provide a different voice and approach from my own.

MQ: And do you think that you can address this matter of respect through architecture?

TB: You have to. You cannot produce architecture solely from your own positions or inner thoughts. This is exactly the reason why I invited all these designers to collaborate in the project. I think it is through these collaborations that you find contrasts and different lenses to look at and address different things. Otherwise, why would we invite people who are not Catholic, or even Mexicans, to participate in the project?

MQ: And “the sacred”?

TB: For me, sacred is my inner necessity to respect other beliefs and views. My work is, in fact, about understanding what is “the sacred” for others—be it religion, society, culture, everyone’s own little world—and providing a space and an environment to support and nurture it.